During the first eighteen months of the pandemic, I filled up ten sketchbooks. It was perhaps my most carefree and productive period of creative growth. When I started, I was bad — and I mean really bad. But I knew that.

I’d always wanted to be a good visual artist, but it was the kind of endeavour that felt so long and daunting I didn’t even want to try. I needed to train classically — whatever that meant. I needed to tackle this thing rigorously, with a course of study. The pandemic, and the accompanying sense that this thing could go on forever, that there might be infinite days locked in my bedroom, gave me space to try.

In those ill-defined and unfilled hours, I pored over my sketchbooks, giving myself what I imagined was an art-school education. I did timed daily figure studies — 60-second snapshots of posed models. They were stiff and poorly proportioned, with scratchy linework. I drew from life — the fruits on the kitchen table, the dog splayed out on the couch, my sister hard at work. I read George Bridgman’s “Drawing from Life,” James Gurney’s “Color and Light,” and Scott Robertson’s “How to Draw.” I worked on perspective, drawing 250 cubes in perspective. I worked mechanical basics like linework, drawing freehand uninterrupted lines from point to point as straight as possible. I did exercises for curves and ellipses in perspective.

And, of course, I sketched as much as possible. It was and still is deeply therapeutic to me, almost meditative: the ultimate form of grounding. Five things you can see, four things you can feel… When you draw, you might spend hours studying the same few objects, noticing everything about them. You are there, with them. I still remember many of the things I sketched during those months, now years ago: the pink duvet folded neatly over the arm of the yellow leather couch in the long-shadowed dimness of early evening. Seared into my memory from thirty minutes of singular attention.

The lockdown afforded me hours and hours every day for focused work. I watched my lines straighten out, my curves flow more freely, my cubes align themselves to the vanishing point. My figure drawings became looser, better proportioned. I learned not to overwork my shading, to respect the large forms rather than muddying them with small details, to define the main value map with the initial lay-in.

I got better, in the freedom and privacy of my bedroom, with the sketchbook as a closed and sacred thing free from expectation.

The pandemic subsided. I moved back to Berkeley. Life resumed, and after a few months my sketchbooks fell into disuse. I still sketched from time to time, but increasingly I didn’t see the point. The consequence-free limbo of lockdown was over, and now, I felt, this investment needed a return to justify itself.

So I started an art Instagram, without a word even to my best friends. I needed to know whether there was a path forward: an audience for my visual art. I followed thirty or so art accounts I admired. I’m ashamed to admit that I spent $30 to boost my posts, to get the ball rolling. I suppose I just wanted someone to like my work — in fact, many someones, no matter who they were, so long as they voted in my favor.

After just a few weeks, I abandoned that endeavour. Admiration and inspiration for other artists’ work had turned to jealousy and discouragement. Instagram had taught me nothing except that everyone was better than me. The drawings I was most proud of looked wilted. They lacked dynamism, they were flat and unimaginative, they were rote. I had arrived at my goal of being a passable artist, only to find that in the company of other artists beyond that threshold, I was totally unremarkable.

I couldn’t see a way of making anything out of my mild talent. So I dumped it. I doubled down on video, where I knew there was a way forward.

I still drew. I still found it therapeutic and calming. I still found ways to challenge myself, like by learning digital painting on my ThinkPad. I even melded video and sketches, producing a few short clips in a series reviewing each week of sketching.

The final nail in the coffin, the thing that really killed my joy, was the arrival of generative AI like Midjourney. When AI art started populating my Instagram feed, I felt my stomach sink. Because now it didn’t matter how good I got, how much time I put in, how rigorous I was with my training — I would never be better than a computer model that could produce hyperrealistic art to precise user specifications in only a few milliseconds.

The truth is that I’m bad at being bad at things. This whole essay is a monument to my pursuit of achievement — my inability to do anything purely for its own sake; my need for milestones, progress, and tangible returns. I compare myself to other people — a lot. And when those comparisons turn out unfavorably for me, I get discouraged. This is a deeply stupid way to go about life — there will always be someone better than me at everything.

I know this. I mitigate this achievement-orientation by finding real joy in process, real joy in the work. But something about the generative AI moment — something about watching my feed flood with unbelievable digital paintings produced by the thousands in the space of minutes, watching AI-generated submissions win art contests, watching commenters debate whether prompt engineering constituted artistic contribution — deflated me like nothing else. It felt to me like the value of the skills I had accrued over years of focused work had just dropped to zero. Not to mention the skills of all the artists more accomplished than me. Rather than commissioning real artists, publications can source their editorial art from Midjourney. The same goes for advertisers, PR firms, and web designers. While this efficiency may be hailed as disruption in Silicon Valley, it feels bleak to me. It feels like automation squeezing the life out of the few remaining avenues for brilliant artists to make a living.

It makes me wonder why we’re building these products at all — was this ever the dream? I thought the dream was to automate all the arduous and dangerous tasks people shouldn’t have to do, not to cannibalize the few truly creative modes of expression left to human artists, underpaid as they might be.

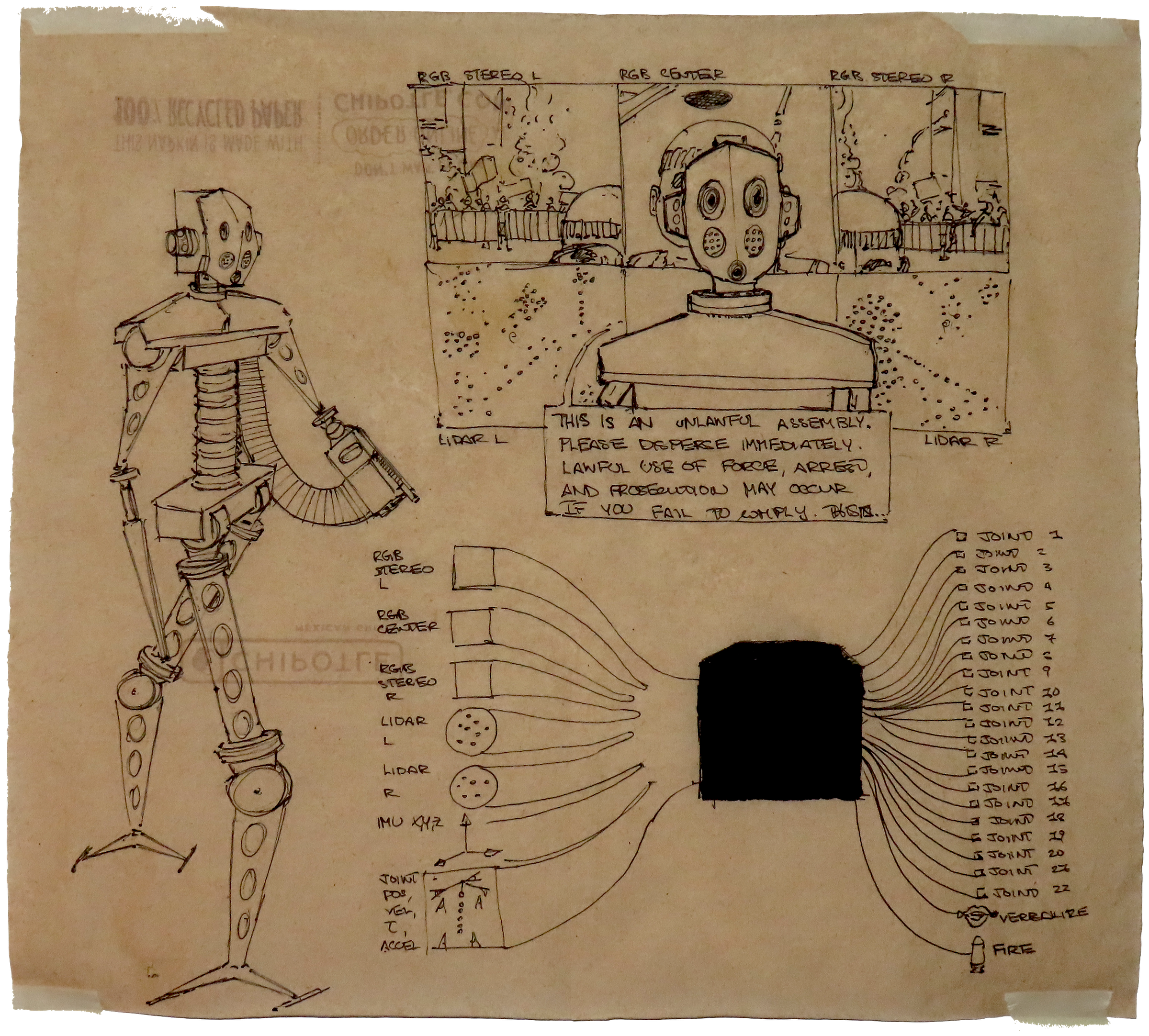

My most successful drawings of late are napkin drawings. The joy of the napkin drawing is that it’s worthless by construction. It was trash before you started, it will be trash when you finish. It represents no expectation, no investment, and no ambition.

As I’m sure most of you who create things have already guessed, my napkin drawings turn out well more often than my drawings in any other medium. I get lucky on napkins far more often than in sketchbooks and far more often than on tablets. Of the seven prized drawings I have taped on my wall, three are napkin drawings.

On napkins, I feel free to experiment. And from that experimentation arises unique style. The argument has been made and I will parrot it here that all AI art is middling. It represents the average of the huge amalgam of styles and subjects on which the model has been trained. Even when prompted to mimic a specific artist, these models return the average of that artist’s work. What makes a Picasso a Picasso is the intensity of his conviction in the specific subject, style, and theme of a given piece. The average of all his paintings is no painting of his at all.

On napkins, and in the freedom from self-censorship they afford me, the freedom to experiment, the freedom to commit wholeheartedly to unique styles, I feel a glimmer of hope.